Process

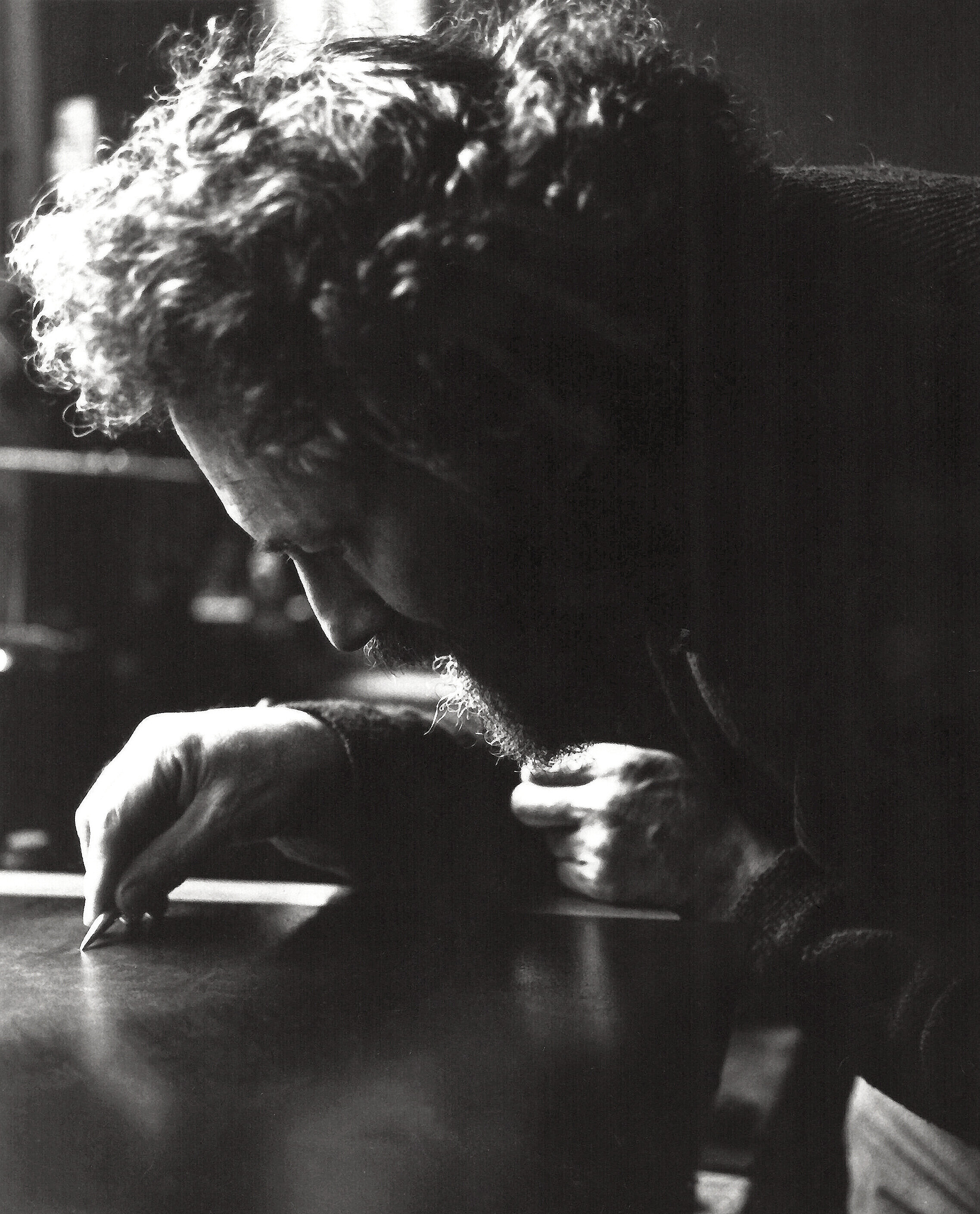

Though Altman worked in various mediums throughout his career, he is best known for his work in lithography and etching. While both processes are based on fairly simple principles of how inks, oils, and water interact, they are highly-technical in nature and require extreme precision and attention to detail.

Lithography

Lithography is a method of printmaking based on the opposition of oil and water. In lithography, a design is drawn with a greasy crayon on a thick slab of polished limestone or specially prepared plate. It is then fixed — or prevented from spreading — by applying a chemical mixture of gum and nitric acid. The surface of the stone is then thoroughly dampened, since the key principle behind a lithograph is the natural antipathy of grease and water. When ink is rolled over the dampened stone, it attaches itself only to the greasy areas of the design. When a piece of paper is pressed against the stone, the ink on the greasy parts is transferred to it. To create a color lithograph, a separate stone is used for each color and must be printed separately. Altman began his journey with lithography printing on limestone slabs. He eventually moved to mylar as his surface of choice. His color lithographs were printed in four passes: one for the tonal range of blacks, and one for each of the primary colors. This means that the range of rich, vibrant colors found in Altman's lithographs came from the simple overlapping of just three colors: red, yellow, and blue.

Etching

Etching is an intaglio printmaking process in which areas are incised using acid into a metal plate in order to hold ink. In order to create an etching, the artist coats a metal plate -- usually copper -- with an acid-resistant etching ground. With a fine needle, the artist then draws a design on the surface of the plate, through the ground, thus exposing areas of the metal. When the plate is immersed in an acid bath, these lines are affected, while the areas covered with the ground are not. This part of the process is known as "acid biting." When the plate is bitten to the artist's satisfaction, it is dried, cleaned of its ground, and inked. The ink applied to the surface settles into the lines or low areas of the plate, and then the surface is wiped clean so that ink only remains in the incised design. Wet paper is then placed on top of the plate, and together they are pulled through a printing press. The great pressure required to pick up the printing leaves a visible plate mark within the margin of the uncompressed paper.

Signing & numbering

Many people ask about the authenticity of a print; what makes a print an original? The short answer is that all prints are originals; that is the beauty of printmaking! A print does not have to be signed and numbered to be original. Signing and numbering prints is a relatively modern practice. The most common method used today is to record the size of the edition and the number of that particular proof on the lower left side of the print. For example, 11/150 means than there were 150 impressions in the edition, of which this is number 11. The signature usually appears at the lower right margin of the print. An artist proof is an impression that is not part of the regular edition. These usually become the property of the artist or the artist's associates (printers, dealers, agents, etc.). Such proofs are usually identified in the lower left margin in place of a number, either as "Artist Proof," "A.P.," or "Epreuve d'artiste."